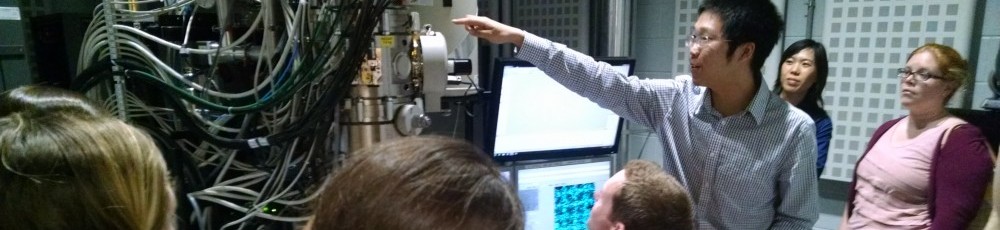

In the May 12th episode of Take-out Science, Dr. Josh Rose, head of the Northeast Chapter of the Dragonfly Society of the Americas, joined us as we looked at dragonflies of all ages. We asked Josh a few questions after the show; his answers are shared below. Watch the episode to see how dragonfly wings look under the scanning electron microscope and learn more about this amazing insect.

Q: Do we know the approximate year/era that dragonflies first showed up? How was this determined? (Are there fossils of dragonflies?)

A: Many biologists consider dragonflies to be “living fossils” because they are remarkably similar to certain insects which existed in the Carboniferous Era, around 300 million years ago. There are fossils, including the largest insect ever discovered: Meganeuropsis permiana, which had a wingspan around two and a half feet across, roughly the size of a crow. The giant fossil insects are not technically dragonflies, though; close study of their anatomy shows them to have some parts in common with dragonflies and others with their close relatives, the damselflies.

Q: What are dragonflies main predators?

A: Many predators eat both adult dragonflies, the flying stage of their life cycle, and dragonfly nymphs, which live underwater. The main predators of the nymphs are fish; some dragonfly species breed in ponds or wetlands that lack fish, and in those settings are sometimes the top predator of the ecosystem, and their main predators are bigger dragonfly nymphs! They do get eaten also by snakes and wading birds (herons, ibises, sandpipers etc.). The main predators of adults are birds, some small hawks like Mississippi Kites and Swallow-tailed Kites make dragonflies large parts of their diets, as do Purple Martins. Spiders also catch many of them, as do many other predators.

Q: Where do dragonflies live? (world-wide?)

A: Since their nymphs live in aquatic habitats, dragonflies can live only where fresh water exists. However, they have stretched this to extremes. Some species get by with tiny trickles of water, or mats of wet moss. Several species are migratory, not so different from Monarch butterflies. One, the Wandering Glider (Pantala flavescens), is such a strong flier that one population apparently migrates from India to Africa and back every year, and others have colonized islands as remote as Hawai’i and even Easter Island. Similar to the way that many butterflies depend on one particular plant for their caterpillars, like Monarchs on milkweed, many dragonflies breed only in certain sorts of wetlands, so there are some species in ponds, others in rivers, others in bogs, some in little spring-fed trickles, a few like mangrove swamps, and so on…

Q: What do dragonflies eat?

A: They are all predators. The aquatic nymphs eat just about anything that moves, from worms and small crustaceans, to frog tadpoles and small fish, to each other. Adult dragonflies eat other flying insects, including mosquitoes, deerflies, horseflies, wasps, bees, butterflies, other dragonflies, pretty much anything that flies. Dragonflies have even been caught eating hummingbirds on very rare occasions.

Q: How long do dragonflies typically live? (What is the typical time spent in each stage?)

A: The flying adult stage never lives a full year, and usually much less, in some species no more than 2 months. The nymphs usually live longer; in some areas, where the nymphs can only feed and grow for a short time each year and have to spend the rest in dormancy to survive long dry or freezing periods, the nymph stage can last for 5 years or longer before it grows large enough to become an adult. This pattern reverses somewhat in a few species like the Wandering Glider, which follow monsoons around and breed in temporary pools created by monsoon rains; their nymph stage has to grow quickly to reach adulthood before their water supply dries up, and it is the adults which may use a form of dormancy to survive through dry seasons until the rains come back.

Q: What are the smallest and biggest species of dragonfly?

A: The smallest in the USA is the Elfin Skimmer, a species found only in peat bogs (Sphagnum moss); it is slightly less than an inch long. The smallest in the world is a species from east Asia named Nannophya pygmaea, which is about 2/3 of an inch long. In North America, the largest dragon is the Giant Darner, which can reach 4 1/2 inches long.

Q: Are there any poisonous dragonflies?

A: Not so far as I know. Dragonflies are one of the most generally edible groups of insects, one of the reasons why they have so many different predators. Also why they are such agile flyers as adults, and so well camouflaged as nymphs, because those are their main tactics for survival.

Q: What is your favorite species?

A: Tough to choose. The Gray Petaltail maybe; it’s one of the more unique species in North America, with several characters that are considered primitive among dragonflies, including nymphs that often leave the water and creep around on nearly land. The Tiger Spiketail is not far behind though…

Q: If you discovered a new species of dragonfly, what would you call it?

A: Hmmmm. Hard to say. Most new species get names that refer to the countries or habitats where they live, people who helped discover them, and other dragonflies which are close relatives. So I probably would have to know more about the species before I could name it.

Q: How did you get so interested in dragonflies?

A: I studied them in graduate school, for my Ph.D. I actually was in grad school for almost a year without being able to decide what to study, none of my ideas seemed like they would work. Near the end of my first year, I went on a birding trip with another student, and one day had a close encounter with a *huge* dragonfly that was boldly marked with blue and green stripes on a brown body. I was really impressed but realized that I know nothing about it. The next day I wandered into a gift shop and found a book about dragonflies there, bought it, read it, and realized that they would work perfectly for my grad school studies. While working on my Ph.D., I spent some time in Texas, and got involved with an annual festival called “Dragonfly Days”. After finishing my Ph.D. I got a job down there in Texas, and one part of my job was leading dragonfly programs. Many of my friends and family have known me as a “dragonfly guy” ever since.

Q: Why should we care as much as you do about dragonflies? (Because they’re awesome?!)

A: They are awesome, and fascinating. The larvae are totally bizarre, with their extendo-arm prey-catching appendage, and how they not only breathe through their butts, but when scared can squirt their breathing water out all at once and shoot off like a little torpedo. The adults are such great fliers, and all sorts of colors, and their eyes are amazing. They eat a lot of insects which are pests for us. And they actually can be important for nutrient flow: nutrients tend to passively run from the land into the water, but aquatic insect larvae like those of dragonflies fatten up underwater and then develop the ability to fly, taking the nutrients from the water back up onto the land. And there are so many different species: even Massachusetts, where I live, has more than 150, each one with its own little specialties and quirks.